Shared by Yonit Naftali

Read more about Yonit Naftali in “A Shavuot Feast Marks the Start of Summer for This Family” and try her recipes for cold cherry soup and semolina and cheese dumplings.

Food writer Yonit Naftali’s first memory of her mother Eva’s fluden and beigli, Hungarian pastries laced with poppyseeds and walnuts, is from dropping off small gift bundles to neighbors for Purim. When she was 10-years-old, she was embarrassed to deliver the packages, called mishloach manot in Hebrew. But, on her rounds one year, a neighbor told Yonit she waited for this special gift. “I remember how my embarrassment became pride. I really remember this moment," Yonit says.

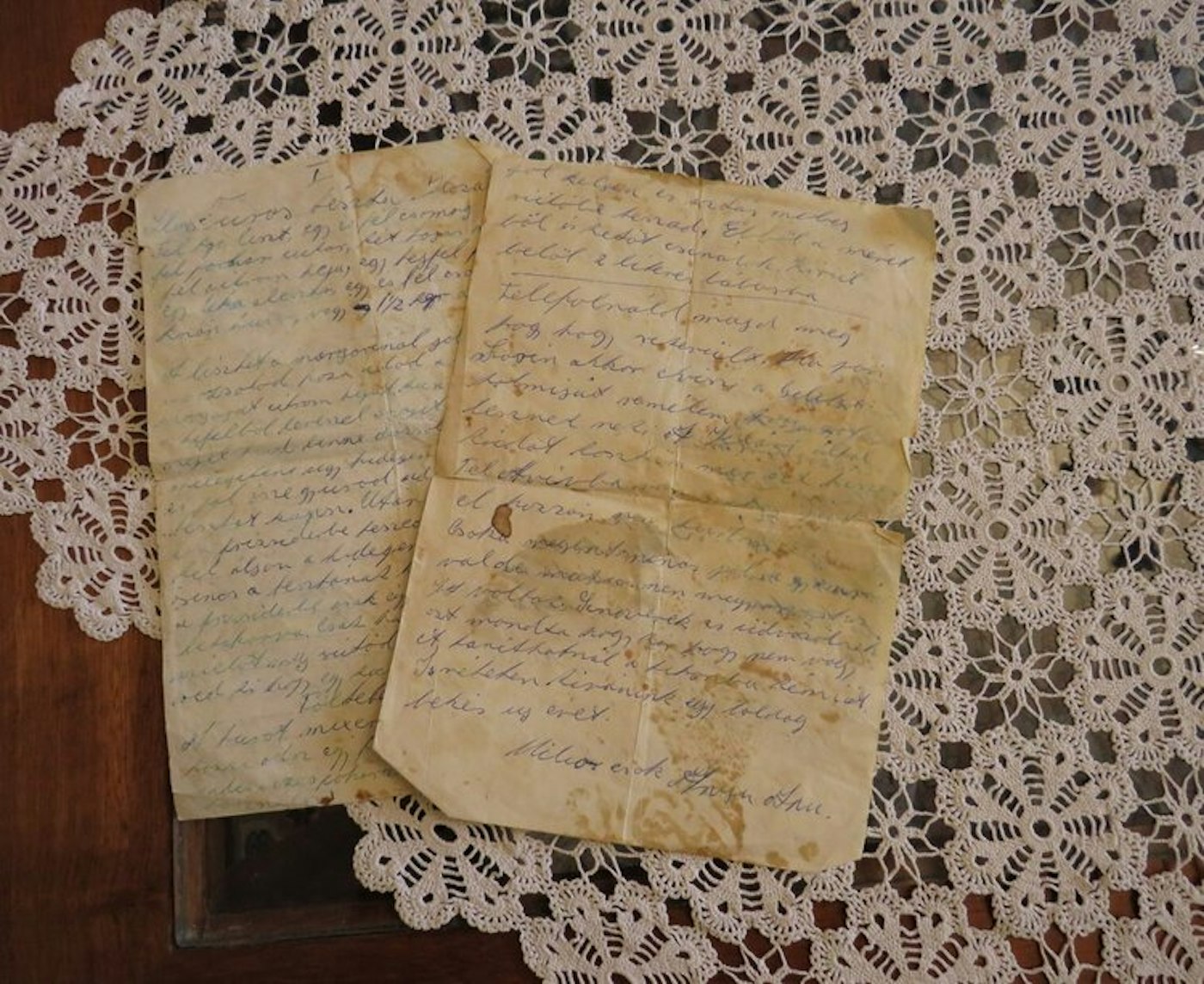

She was proud of her mom and her recipes, which go back generations to the family’s roots in Transylvania, in a town called Oradea that was previously part of Hungary and today sits within Romania’s borders. “After the Holocaust we had nothing. There was nothing left, no one left. And, the only thing my grandma [Paula] remembered accurately is the recipes,” Yonit says. “It’s the only thing [my mother] has that is left from her family, from her tradition.”

During World War II, Paula and her family were deported to Auschwitz. There, most of the family perished, but she survived. After the war, Paula returned to Transylvania where she reconnected with Paul the brother of her late husband Miklosh. Paul had lost not only his wife Margit, but the family believes their children Paul and Tibor as well (Eva continues to look for them today). Clinging to any remnant of family, Paul and Paula were married and started to build a new family together.

Hoping to move to Israel, the family struggled to leave Transylvania until a particular day in the 1960s when Paul went to apply again for a permit to leave the country. At the office, he met a representative from Israel who was there to assist with Aliyah. The two men didn’t speak the same language, but the representative said to Paul: “l’shanah habah b’Yerusahalim,” the Hebrew saying from the end of the Passover Seder that promises next year will be in Jerusalem. Paul understood and returned home to share the news, along with two Jaffa oranges.

The transition to their new home was hard. They were sent to a resettlement camp in Afula in the north of Israel. Paul was a trained maître d' and Paula a skilled seamstress, but there was no work for them in the camp. After six months, they managed to move to Nahariya where Paula found work making dresses for wealthy neighbors, many of whom she became friendly with. When Paula passed away years later, it was these women who helped take care of the funeral arrangements, Yonit explains.

Eva has kept Paula’s Hungarian recipes alive. In their family, each holiday has a special dessert. For Passover there’s a torte made with nuts and egg whites, layered with chocolate ganache. At Shavuot, there are cheese dumplings made with semolina and lemon zest; for Hanukkah, it’s yeast doughnuts with brandy or wine mixed into the batter. And for Simchat Torah, Eva makes a cake called arany galuska with a yeasted dough enriched with milk.

Today, Eva no longer makes mishloach manot for the neighborhood, but she still bakes for her children. Using one batch of dough, she makes the beigli, a log pastry filled with poppy seed paste or walnuts and the layered fluden, which repeats the use of walnuts and poppyseeds and adds a layer of apples. In the family, alcohol is always added to the dough. Her mother jokes, that in keeping with Purim’s tradition of drinking, “you should even make the dough drunk.”

In Eva's home, the recipes are unchanged from Paula, she continues to mix the dough and grind the nuts by hand “My mother never changes the recipe from what her mother gave her,” Yonit explains.