Shared by Léa Karsenty

“You had to be very strong and have a big voice to make yourself heard,” Léa Karsenty says of the matriarchs of her family. “It’s not a condition they chose,” she clarifies. The legacy started with her great-great-grandmother, the mother of a dozen children or more — the exact number has been lost to time — who left an abusive husband in Morocco, generations before it was common. “That’s her story, so I feel it started with her,” Léa adds.

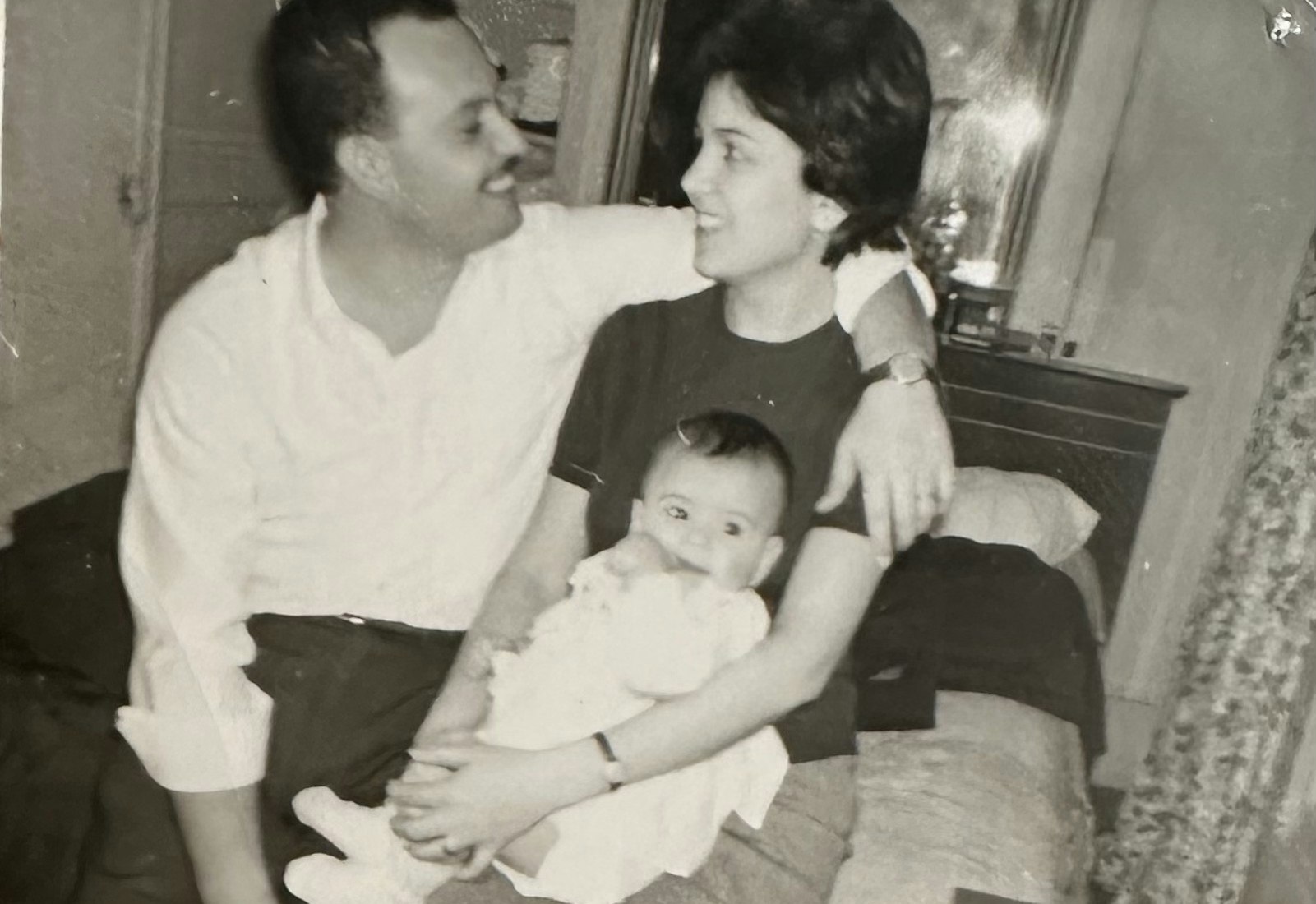

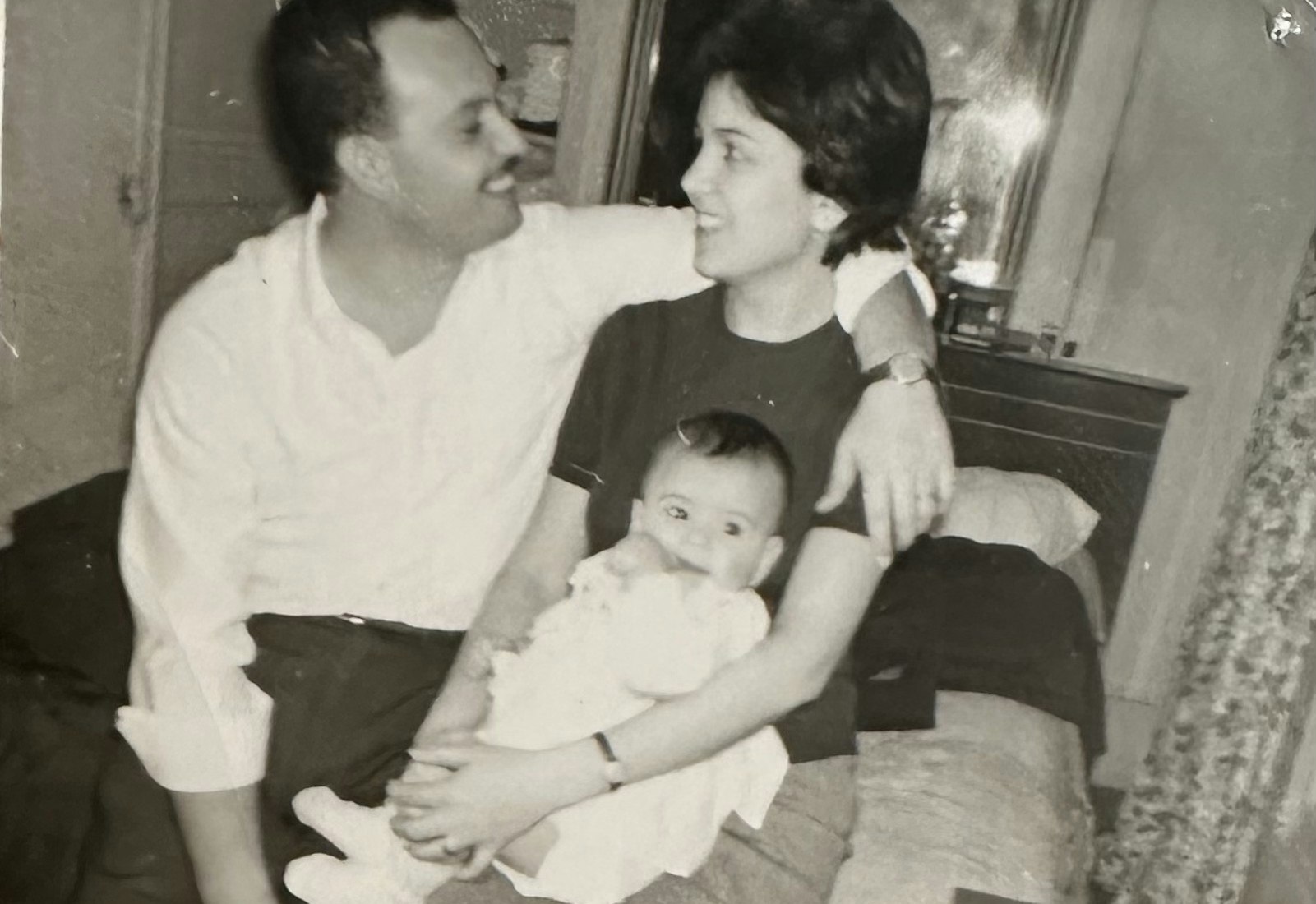

Mamie Marie, Léa’s great-grandmother, was one of those children. “All the stories in my family are about her. She’s the queen of the family. We always talk about her [and] she always had stories to tell — most were invented,” Léa explains. Her daughter, Sara — another strong woman with a powerful voice — was born in a small Moroccan town and lived in Algeria until 1962 when the country declared independence and she moved as a new mother to France.

The family’s best recipes come from these women. Many are traced back to Marie and were passed down to Sara who makes several of them for Erev Yom Kippur. It’s the one holiday where she hosts the entire family at her home in Toulouse in the south of France, Léa explains.

To prepare for the high holidays, Sara buys around 10 chickens and uses them for the tradition of kapparot — a medieval Jewish custom where chickens are passed over one’s head in an atonement ritual. She then invites a rabbi to her garden to slaughter them, before plucking their feathers and cooking dishes like roasted chicken with paprika and cumin, chicken soup with saffron and toasted pasta, and chicken thighs and beans in a spiced tomato sauce. She also makes a salad with artichoke hearts, along with dishes of cumin-laced fava beans and fried eggplants with preserved lemons.

Everyone in the family — cousins, uncles, and aunts — is invited to the meal, but “after dinner, all the boys leave,” Léa says. Generations of women stay and talk for hours. “It’s a really great moment that happens only once a year — there are no phones and we are really focused on talking; we don’t have anything else to do, but stay for hours, sitting at the living room table.” Every year, as Léa and her sister walk home late at night, they say it’s the best night of the year.

The next day, after services at the synagogue end, the entire family walks to Léa’s aunt Caroline’s home for a break-fast of desserts, many of them made by Sara like her famous vanilla candied oranges, mouna or sweet pockets of dough stuffed with almonds and raisins, and makroud, a North African dessert made with semolina and stuffed with dates and hazelnuts. There’s also always her signature challah studded with anise seeds.

During the pandemic, Léa started to learn her grandmother’s recipes — mostly over the phone. “She describes every inch of the recipe,” Léa explains. But when it came to the challah, Sara insisted Léa learn the recipe in person.

Léa’s inherited much more than the recipes from Sara. “Everybody always says I’m voice-y like my grandmother,” she notes. “If I'm as strong and smart as her, I think that’s the best thing that can happen to me.”